In 2015, Myanmar was ranked the world’s most charitable nation by the World Giving Index. For those who live here, this isn’t necessarily surprising. When major flooding hit during the monsoon season last year, the community mobilized immediately. Students organized volunteer efforts, donation groups patrolled the streets soliciting donations from cars and pedestrians, and trainers at my gym interrupted my lat pull-downs to show off pictures of the rice they’d delivered to affected villages. The environment was humid with donation. This is how Myanmar operates. In a country where government-provided social services are found wanting, the people are contributing to sustain the country. Young and old donate to keep hospitals, monasteries, orphanages, and nursing homes operating. Donation as a virtue is ingrained in the culture, even the highway bus stop bathroom has a plastic basket full of soggy 50 kyat notes. But donation here is even more than that. It’s not merely a virtue that nags the edges of consciousness from time to time. It is seen by many as a regular activity, a serious hobby. Something that you think about, plan, and consciously participate in.

The seriousness of Myanmar donation hit me on another level during one of many heart to heart chats with Yangon’s taxi drivers. We were discussing hobbies, and the driver mentioned to me that donation and reading are his favorite hobbies. During the week he gathers donations and volunteers, and on the weekend he takes a crew to deliver the goods to those with a need. He is always looking for resources to donate and people to share the experience. The conversation with this taxi driver struck me as odd. This guy was talking about donation the way someone in the West would talk about golfing, the way I talk about rock climbing. My idea of a donation is a quick bank transfer to a humanitarian agency, or some small bills quickly handed to the woman on the corner. . . When he dropped me off at my stop he asked me if I wanted to go donating with him over the weekend. . .”Um, what’s your name again?”. . .”Pyae Sone.”

That Sunday morning, Pyae Sone picked me up in his taxi, and we drove outside Yangon to Thar Bar Wa Center to do donation.

As it turns out, Myanmar donating is a somewhat personal activity. I expected that we would bring the items/money to a central office for distribution to the residents at a later time. What really happened was that Pyae Sone had arranged for 300 food packages to be individually wrapped. We wandered through the patchwork shelters that house people living with old age, mental health disorders, developmental disorders, HIV, and TB, handing each individual a food packet until there were none left.

A mother washing laundry for her son, a resident at Thar Bar Wa

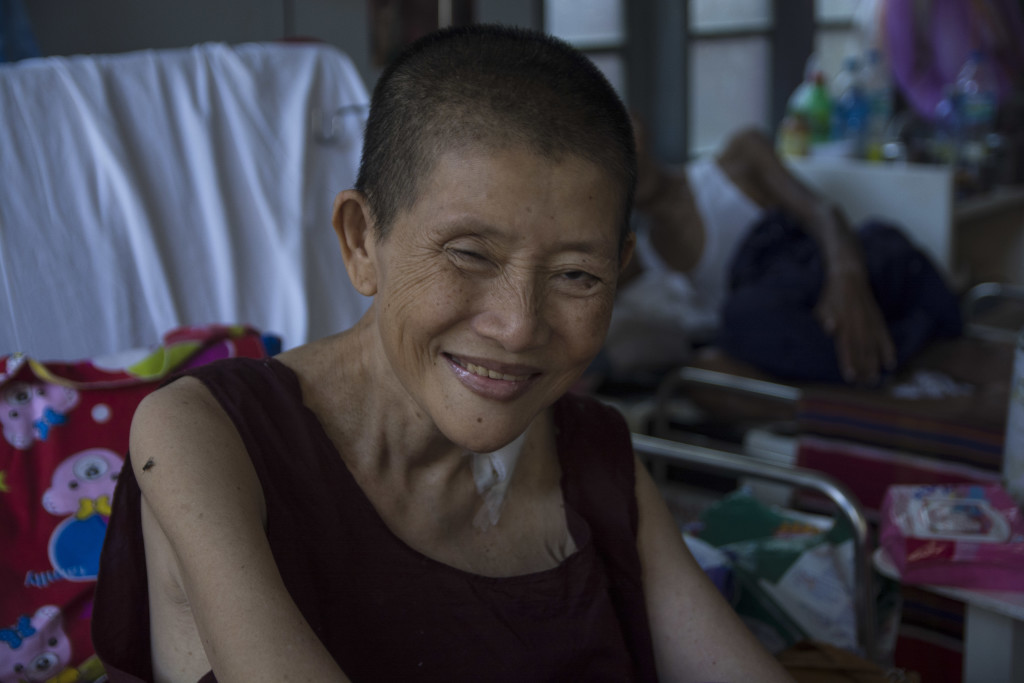

Posing for the camera

The eldest resident at Thar Bar Wa, wanted me to sit next to her. She is 106 year old.

Thar Bar Wa is a home for all who are homeless, sick, and wandering. Currently, 2,600 residents of all religions, nationalities, and conditions are staying at the center free of charge. People have come not only to find healing from physical illness, but also spiritual care through rest and meditation.

Before we left we were able to have a short conversation with the founding monk of Thar Bar Wa, Sayadaw U Ottamasara. He had this to say about the struggle and rewards of running the center:

“Sometimes I am very tired. The problems here are many; they will never end, but this place is not about the political power. It is about the power of people around the world to contribute. When we give for people’s needs it increases the overall power of giving for people’s needs. Many people are solving problems only with their brain, but I am solving with my heart. Our lives, we do not own. We are only passing: I want to pass it helping other people.”

As is usual in my interactions with the world’s unregarded people, I walk away from Thar Bar Wa with the sense that I received more than I gave, that I learned much more than I taught: A dichotomous sense of the weightiness of my privilege, and simultaneously a sense that I am on the right path. I wonder about how the world could be different if we valued the things that these people could teach us about ourselves.

“If you spend yourselves on behalf of the hungry and satisfy the needs of the oppressed, then your light will rise in the darkness, and your night will become like the noonday.”

If you’re interested in finding out more about Thar Bar Wa, you can find them here.