This is a post containing reflections and photos concerning the six months I spent in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. I’m planning on also posting something about my work with the Rohingya refugees after I feel that I have acquired sufficient words to share their story. DISCLAIMER: This post has some potentially disturbing photos of a cow being sacrificed for Eid.

Cox’s, Bangladesh

I lived in the far South of Bangladesh in a “seaside tourist destination” called Cox’s Bazar. The term “seaside tourist destination” is perhaps deceiving. Please suppress the images of tourists strolling down white sand beaches in their swimsuits relaxing and enjoying a carefree vacation. Although for Bengali nationals this image is near accurate, for anyone not possessing the complexion of a South Asian, it is far from the truth. For myself and others of a similar complexion, “strolling” on a beach in Bangladesh entails 30 Bengali locals following you, taking pictures of you/with you, asking what your country is, how much money you make, what your religion is, if you are married, and what your father’s name is, Oh yes and would you also like to buy a boiled egg? Similarly different, “Swimsuit” in Bangladesh refers to a full burka/shalwar kameez for women, while jeans and a button-up t-shirt are the established swimwear for men. So, if you did not manage to suppress the images of people strolling on white sand beaches in their swimsuits, you are in for just as big of a surprise as I was. . . Although I seem to be wrong every single time, I still manage to superimpose my own expectations on countries before I get there.

Around Cox’s

Sayeman Pink Pearl Building, our home in Cox’s

This guy made me omelets and chapatis every day for breakfast

Saint Martin’s Island

Transit to the nearby island of Maheshkhali

Being white

The lesson of the Bangla beach brings me to the glaring unavoidable truth. There is no getting out of it; I am, without a doubt, white. Duh. So I’ve known that I’m white (I even had an entire class in graduate school dedicated to thinking about how I was white [is this weird to talk about?]), but when the marker of your alien nationality is in fact associated with: inflated prices, people’s stares, constant good-natured albeit exhausting questioning, and not-so-discretely-taken photos, whiteness takes on new meaning. The amount of attention I received as a foreigner was moreso in Cox’s Bazar than anywhere else I have been in the world. In my first week I grew tired of the invasiveness so much so that one of the first Bangla phrases I learned translates to, “don’t look at me; I’m not beautiful.” Whereas in the United States being white didn’t necessarily mean anything significant to me, my skin color (in association with my foreignness) was a very strong factor in many of my every day interactions in Cox’s Bazar (all of my friends who are ethnic/racial minorities feel free to give a knowing nod at this point).

Ramu

Banglatality

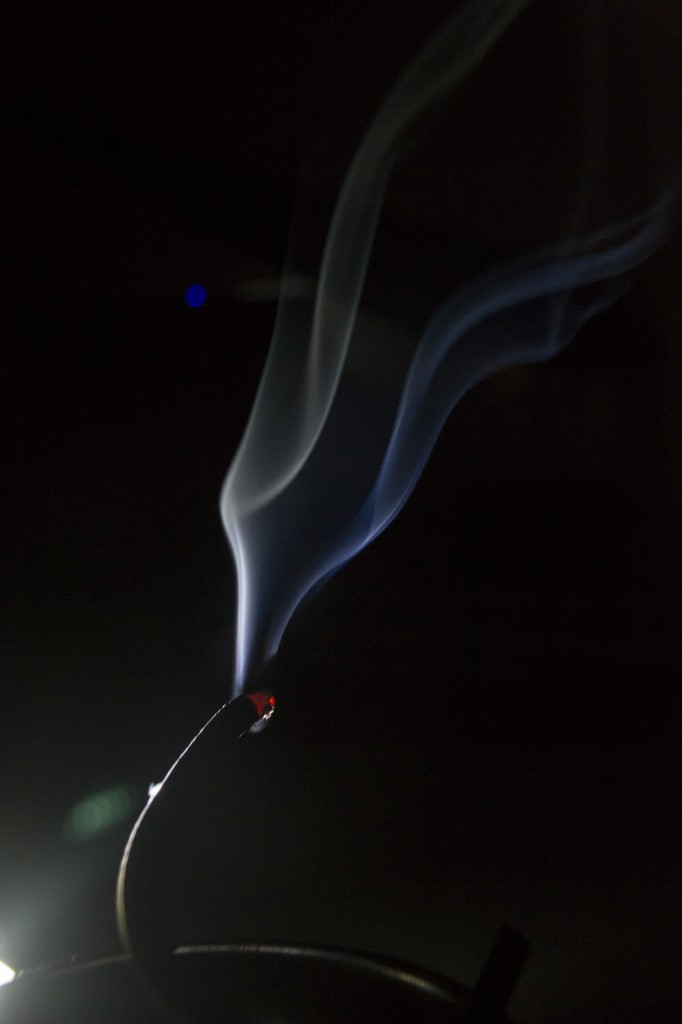

Bengali people in general are some of the most warm, welcoming, and helpful that I have encountered in Asia. The brightest memories of Bangladesh are at the houses of the National Bengalis who I worked with: Lounging at Dr. Taimur’s house on a Saturday afternoon, hanging out at Samsul’s place and watching his neighbors slaughter their cow for Eid, and going to Russel’s place for lunch; where his three-year-old son Jawad would repeatedly kill me with a plastic gun and then do CPR on me until I woke up. These memories with the staff and my work with the refugees (a story for another day) are what I value most about my Bangladesh experience. It is impossible to really represent the Bangla experience in a single post, but here are a list of things that made up daily life in Bangladesh: cold showers, amazing tea, incredible South Asian food, sketchy internet, nescafe instant coffee, mold growing on clothes, puppy season, beach bike rides, surfing, not knowing when things were happening, eating “manually” (with my hand), speaking Banglish, learning to play the guitarish, the drama that was my bicycle, making fun of Andrea with Nathan, learning to tollerate bollywood, becoming accustomed to over-service, large roaches, abundant mosquitoes, the ridiculous practice of Cox’s Bazar weightlifting, living in the Pink Pearl, the couchress, playing pool with the surf guys, crazy times at Seagull Hotel, the call to prayer, colorful/beautiful/chaotic religious festivals, and–most iconically–riding in rickshaws.

Fire-spinning at Mermaid

Durga Puja

Eid

Paradoxical Interaction

One of the enticing things about living and working internationally is the steady building of a kind of social credibility. Upon first arrival in developing countries, I have consistently experienced a tourist scarlet letter. Typically, the value that the local people initially allocate to me is linked to the amount of money I am willing to spend (which is not very much). The tourist scarlet letter comes with the following assumptions: I will be buying things from street vendors at an inflated price; I will be staying in a upscale hotel separated from the lifestyle of the local people; I will be driven around in the nicest vehicle available; I will only speak English; I have an unlimited disposable income; and I will not be staying in the area for very long. The beauty lies in the fading of these assumptions. The longer you stay in a country and, more importantly, the more you engage with individuals, the more things begin to change. It usually works something like this: I meet some people. I learn some Bangla. I speak Bangla with the people I met. I drink tea with neighbors at a fascinatingly dingy tea stall. I take the public transportation. I ask one of the people I drink tea with to take me somewhere in his rickshaw. The result, I get to pay the local price for the rickshaw without argument because we know each other. This is a small victory, but it’s not because I saved 10 taka. These small cultural growth victories culminate in simple, beautiful, and (most importantly) paradoxical interactions. My favorite of these was with a street child near the end of my time in Cox’s. I was on the beach, and street children in Cox’s often stay on the beach and ask tourists for money. I was approached by a street child who looked like he was about eight years old. Generally, in this situation, I slip into that awkward interaction mode of avoiding eye-contact while a million questions explode in my head: Should I give money? Should I give food? If I give money will he become dependent on hand-outs? If I don’t will he starve? Will he spend it on drugs? Does he go to school? What do his parents do? Is he homeless? Can I just tell him about my massive, looming education loans?? Instead of asking him any of these questions, I used Bangla to ask his name. We started communicating in broken English, broken Bangla, and hand gestures. After about 5 minutes of this he produced some sugar cane from a bucket, and he (the street kid) offered me (the supposedly-rich, scarlet-letter-bearing-foreigner/probable tourist) some sugar cane. I accepted it, and we ate sugar cane together while we continued communicating. We both went our own ways. He never asked me for money. I take away so much satisfaction from such a simple interaction because it transcends the traditional roles and rules that govern how things are supposed to work between locals and foreigners. The assumptions of the tourist scarlet letter so briefly disappeared. We moved past those assumptions to a more human level. That is the only time a street child has ever offered me anything for free. Several other interactions like these happened near the end of my stay in Cox’s, but the paradox of the sugar cane event is my favorite.